Global value chains (GVCs) are the arteries of international commerce, enabling trade flows worth tens of trillions annually in merchandise and services trade alone. Today, more than two-thirds of world trade occurs through GVCs. In 2017, the expansion of complex GVCs was faster than GDP growth. When we talk of global trade it has become imperative to talk about – and look into – the operation of GVCs.

These complex ecosystems engage the largest multinational corporation (MNC) to the smallest enterprise and are the source of large global investment flows and economic value creation. However, while MNCs account for about one-third of global output and world GDP, and half of global exports, the participation of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in GVCs is far more limited.

Why is that the case?

In large part, it is due to SMEs’ lower scale efficiencies, perceived risks due to a lack of rigorous processes to ensure ethical behaviour and sustainability, and reduced access to finance for new investments and technology. This hinders their potential to connect to GVCs and therefore to add extra value to their exports and the global economy.

With the world economy experiencing and facing significant disruptions, from financial crises and “trade wars” to natural disasters and virus outbreaks, GVCs have been in constant transformation. While past decades fostered an expansion and enlargement of GVCs, in more recent years some have also shortened and become more localised.

These changes have been driven mostly by increasing risks from a world that is not just more interconnected but also more unpredictable. MNC executives around the world are constantly assessing and searching for the best ways to de-risk their global operations while maintaining value in their supply chains. However, while there may be valid commercial reasons to shorten and localise supply chains in many cases, doing so purely for ease of addressing supply chain management may also reduce the potential for value creation or have other unintended economic or risk consequences.

A more recent category of risks for those operating within GVCs has emerged in recent years: namely, risks associated with ensuring integrity standards in supply chains.

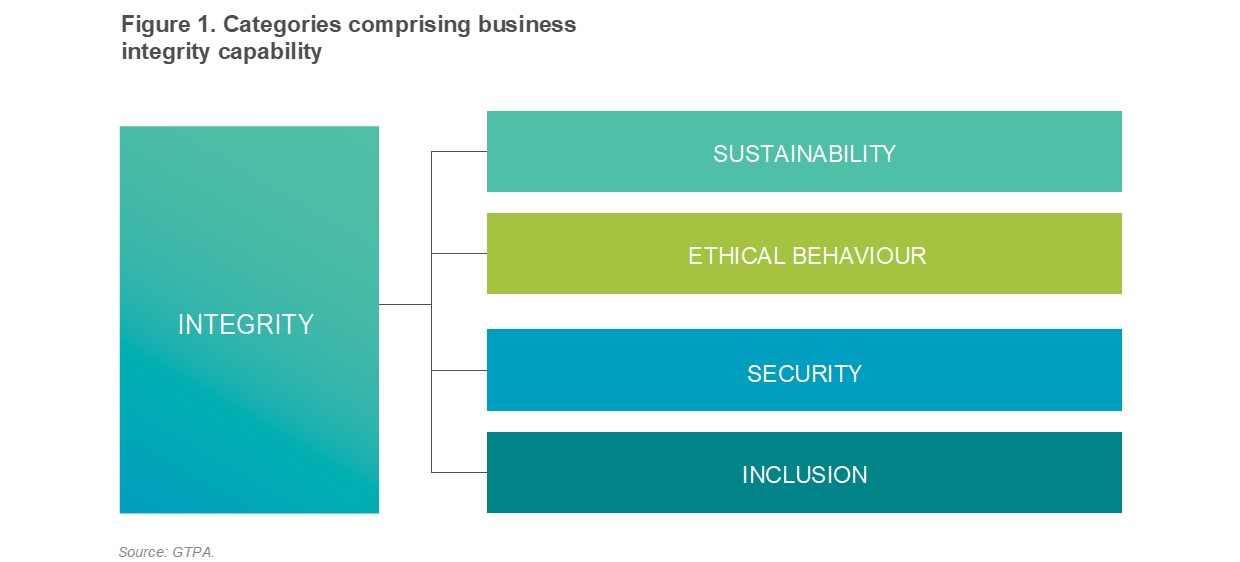

Integrity is the capability of businesses to ensure sustainability, ethical behaviour, security and inclusion throughout their entire operations across GVCs (see Figure 1 and Table 1 in Appendix 2). Large businesses that rely on a social licence to operate, which is the case for the majority of businesses around the globe – and especially for renowned MNCs – can no longer ignore the pressures of a socially engaged world.

As consumers have become more socially conscious, so too have investors who are increasingly seeking closer scrutiny of the integrity of GVCs both to protect their investments as well as to use their investor influence to improve integrity-associated outcomes. As has been clearly stated in a recent publication by the OECD: “The integration of global economic systems goes hand-in-hand with the integration of global social and environmental impacts.”

Ensuring integrity, thus, is now viewed as essential to a corporation’s global responsibility. Even more importantly, failure to do so is a potential brand risk or supply chain disruption.